The proposed legislation could create an untenable position for search engines in Australia, and Google’s threat to shut down search could affect traffic and domestic businesses across sectors.

While the two situations both involve Google and publishers, Australia’s proposal carries wider implications for businesses outside of publishing and possibly even other search engines. And, should Google have to carry through on its threat, there may also be unintended consequences for domestic businesses.

The situation in Australia

In April 2020, the Australian government asked the Australian Competition & Consumer Commission (ACCC) to draft a compulsory code of conduct to address bargaining power imbalances between digital platforms, specifically Google and Facebook, and Australian news media businesses. That code of conduct became the News Media Bargaining Code.

How it’s different from the French deal. The deal in France serves as a foundation for licensing agreements with individual publishers. The agreements will fall under Google’s News Showcase initiative, in which the company pays publishers to license their content, displaying it to users within a story panel.

Google’s deal with French publishers does not extend to traditional search results. Australia’s Code, however, does seek to compensate publishers for links within the traditional search results.

For Google, it’s not just about compensation. “Our issues with the current version of the Australian Code are not about money, we’re willing to pay,” Google said in a statement to Ars Technica.

“It’s about being asked to pay for links and snippets which EUCD (and the French transposition) does not. This is where we draw the line. Links and snippets are the building blocks of the free and open web. To pay publishers in Australia, we’re proposing to do the same thing we’re doing in France – to pay publishers for value with News Showcase. The difference would be that News Showcase would operate under the Code, that means publishers can go to arbitration on News Showcase to solve any disagreements,” the statement reads.

In addition to opposing payments to publishers in order to link to them within the main search results, Google has also objected to these other Code stipulations.

- Providing advanced notice of algorithm changes: Google would have to give news publishers 14 days’ notice of certain algorithm changes. This would “give special treatment to news publishers in a way that would disadvantage every other website owner” and delay updates for users, the company said.

- The arbitration process: Should Google and a publisher fail to reach an agreement, the arbitration process only calls for arbiters to weigh the publisher’s costs to create content and the benefit it receives from Google, overlooking what it costs Google to provide search results. Additionally, baseball arbitration, which requires both parties to submit a final offer from which arbiters select one of those submissions, will be used to decide how much Google would pay.

The U.S. Chamber of Commerce and Executive Office of the President have both submitted documents to the Australian Senate Standing Committee on Economics expressing concerns over the imbalanced arbitration model and the Code’s sweeping measures that only target two U.S. companies.

For Australian regulators, it’s not just about the money, either. “[Google and Facebook] have been selected on the basis that they display Australian news, without typically offering revenue-sharing arrangements to all news media businesses that produce this content,” the Code states. However, this same statement could be applied to other search engines and social media platforms, suggesting that compensating publishers is not the only factor at play.

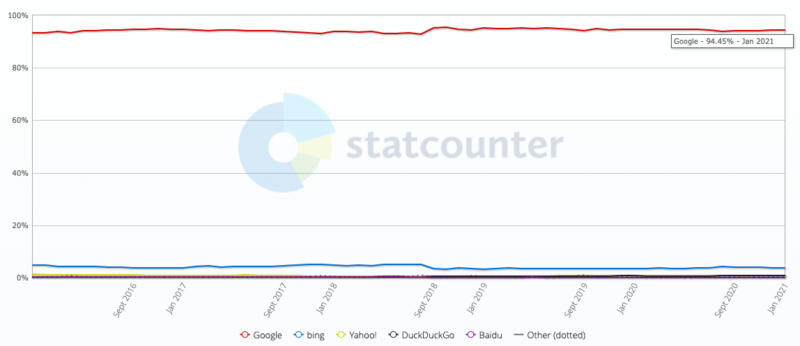

In Australia, Google accounts for 94.45% of the search market, according to statcounter, with its nearest competitors, Bing and DuckDuckGo, accounting for 3.61% and 0.85%, respectively.

Google’s dominant position means that it has immense influence over entire industries as well as how people access information. Historically, only governments have wielded this much influence, and the ACCC may also be seeking to curtail that influence by exerting its own authority, via the Code it recommended, over Google and Facebook.

“Without strong regulatory intervention, the sustainability of a diverse local media sector is at risk and our society could be beholden to decisions made by two men in Menlo Park and Mountain View,” Chris Janz, chief digital publishing officer at Nine (the publisher of the Sydney Morning Herald, the Australian Financial Review and The Age), said in a statement to the Australian Senate Standing Committee on Economics.

On January 13, it was reported that Google conducted an experiment in which it removed media sites from Australian search results. “Instead of receiving critical updates from the ABC, 9News, The Age, The Sydney Morning Herald or The Australian, some people searching for ‘coronavirus NSW’ received just a single news story at the top of their results – a three-week-old update from Al-Jazeera,” Janz said.

“Google’s ability to execute this so-called experiment demonstrates a truth at the core of the digital media ecosystem: you either play by their rules or not at all. For media organizations this means having to accept your content appearing on Google’s platforms. This provides Google with significant commercial returns without paying a single cent for the creation of that journalism. If you don’t play ball, Google has shown they are not afraid to effectively make you disappear from the internet,” he said.

Little more than a week after that, Google threatened to remove search in Australia if the Code were to become law. In response, Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison said in a press conference, “Australia makes our rules for things you can do in Australia. That’s done in our parliament. It’s done by our government. And that’s how things work here in Australia and people who want to work with that, in Australia, you’re very welcome.”

It’s all about precedent

Negotiations between the Australian government and Google have resulted in a sort of brinkmanship that, unless the two find an alternative resolution, is likely to affect how search engines work (at least in Australia), the relationship between content creators and search engines and test whether either party is willing to carry on without the other.

Google has pulled the plug before, but never like this. Google is no stranger to regulatory pressure from governments and publishers. In 2014, it compelled German publishers to formally opt-into Google News following the enactment of a copyright law that gave publishers near-total control over the use of their content. It later limited German news content to headlines in order to avoid liability. Later that same year, it shuttered Google News in Spain following the passing of an even more extensive law that did not allow individual publishers to waive their copyright licensing rights.

However, those responses are a far cry from turning off search entirely. Although that is a drastic measure, Australia is a fairly small market, so withdrawing that part of its business may be a more cost effective decision than paying to link to Australian publishers and broadcasting that it’s willing to do the same in other markets.

The collateral damage from shutting down Google search. “I predict new user traffic for smaller sites that are driven by a lot of discovery via organic search will drop off substantially,” said Matthew Brown, managing director at MJBLabs and former director of search strategy for the New York Times, noting that larger media organizations are likely to fare better because people may seek them out directly.

Even so, organic traffic is almost certain to decrease for publishers across the board. And, fewer visitors means fewer revenue opportunities. “Publishers would lose detrimental amounts of traffic, especially when many media businesses rely on traffic for programmatic and direct sold advertising,” said Ben May, CEO at The Code Company, an Australian development agency that works with online publishers.

“Many businesses would go under,” Colm Dolan, CEO at Australian programmatic advertising technology company Publift, told Search Engine Land, adding, “There are many other content providers who do not fit this bill. There are infinite other e-commerce, product/service based businesses who get most of their sales through Google search.” If Google withdraws search, it may, at least initially, sever ties between many businesses and their audiences.

No matter how this unfolds, other countries will be paying attention and Australia will serve as an example of how far Google can be pushed before it begins pulling levers to protect itself, and those same levers may even have unintended consequences for their domestic businesses.

Australia without Google search. The sudden departure of the foremost search engine might cause publishers to increase efforts in other marketing channels. “Publishers would be under immense pressure to build direct audiences or subscribers, a lot of publisher focus will move to apps, an ecosystem where it is easier to build subscribers and returning users,” said Ankit Oberoi, CEO at ad optimization company AdPushup.

This strategy may help insulate publishers from the fallout of Google’s hypothetical retreat from Australia, but users will still need a way to search for whatever they’re looking for. The options available to users would then be using a VPN to access Google, or switching search engines.

If users turn to VPNs, “consumers would get their information from U.S./UK publishers which could potentially take revenue out of Australia,” Dolan said, adding that this would send traffic away from domestic publishers.

“If Google indeed shuts down in Australia, and most of the users shift to another search engine, wouldn’t the same issue happen with Yahoo or Bing?” said Oberoi. Although Microsoft has already met with the Australian prime minister and expressed interest in expanding its presence there, it is unclear whether other search engines would be subject to the Code.

If Google acquiesces. Google paying to link to publishers “will change how the internet works and how the value of content is derived,” Oberoi said, “Their margins will take a big cut, [and] Google will probably relook at how the search listings work, perhaps prioritizing open-source like content where the content creator is voluntarily not expecting money.”

In the short term, publishers will benefit, but not all of them. “The current proposal I feel is greatly flawed,” said May, “It disproportionately helps larger media companies [over] smaller organizations.” This is because larger publishers are likely to have greater bargaining power. And, depending on the magnitude of compensation publishers receive, it may make them even more reliant on search engines to support their bottomline.

It is also conceivable that a paid inclusion model may enable publishers to pursue legal action against Google. “Paying publishers for inclusion gives precedence to legal battles if something happens to a website’s rankings,” said Pedro Dias, head of SEO at British publisher Reach PLC and former search quality analyst at Google. If a site isn’t ranked anywhere near the top, the publisher may attempt to argue that they are essentially not in the index. “Google should be able to adjust their quality criteria according to their users, and not be subject to being legally challenged because of a commercial agreement,” Dias added.

Additionally, Google also benefits from searches outside of the news vertical, and the creators of that content are not being compensated for the value that Google is able to extract from them. If one industry in one country is able to bend Google to its will, the way publishers in Australia are attempting to, it may open the door for other industries to organize and make similar demands.

Will the remedy be worse than the issue?

For Google, the primary issue is paying for links in its main search results, and the precedent that would set. For Australian regulators, the issue may be about Google’s influence over its society and businesses as much as it is about struggling publishers. However, if the Code, in its current form, becomes law, it may end up favoring larger publishers over smaller ones and providing one vertical with an inherently unfair advantage in the search results.

If Google reneges on its threat to shut down search and pays to link to publishers, it will be opening up a floodgate that could result in a cascade of similar legislation around the world. If it has to carry through on its threat, then businesses may also suffer as Australia shifts to an alternative platform, where the cycle might eventually repeat itself.